This Old House

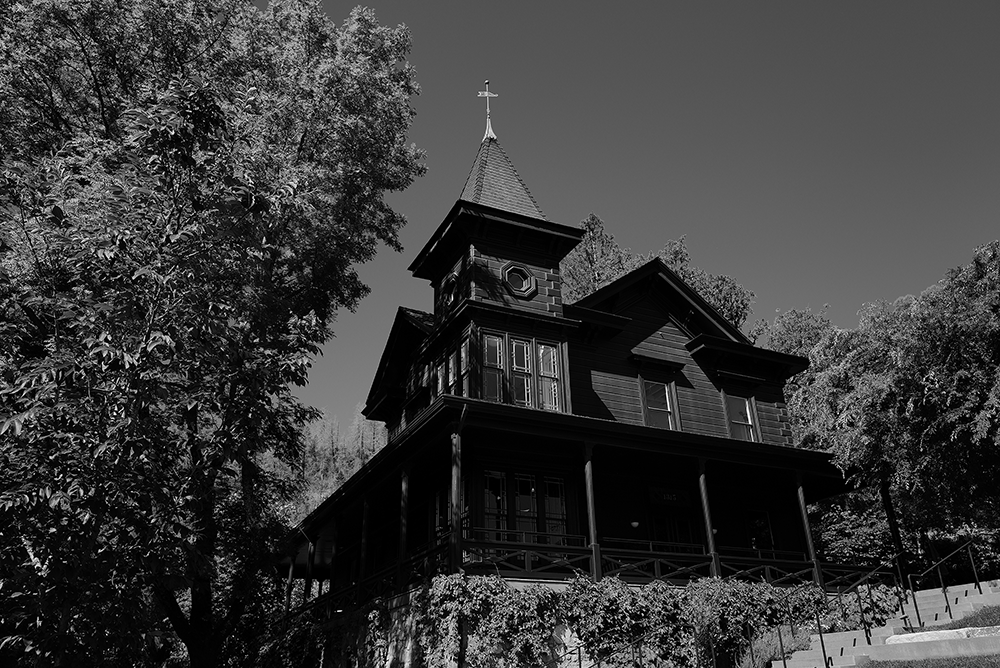

IF YOU’VE EVER REMODELED a kitchen, added a wing, or redecorated your home, you know that a house is never set in stone (as solid as its foundation may be). It’s a living, breathing thing, much like the people who inhabit it. Consider Faust Haus. We like to think of it as a welcoming home, the kind whose doors are always open, whose guests fill it with life. But it hasn’t always been that way. The history of this house has, at times, been as dark as the matte-black paint that now adorns it.

Let’s go back to the 1870s, about 25 years after California achieved statehood and the Bay Area was transformed by the Gold Rush. As detailed in “King Cab,” on page 4, some of the Napa Valley’s most respected and successful names, from Charles Krug to Schramsberg, had established a foothold here in the 1860s. By 1889, there were more than 140 wineries in the Valley.

The growth of the area was, perhaps, inevitable, given the money and bustle of San Francisco, booming from the influx of gold seekers. San Francisco surged from a town of 500 in 1847 to a city of more than 150,000 in 1870, attracting the likes of Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson, and the construction of Golden Gate Park in 1860 by Frederick Olmstead.

Among the valley’s arrivistes was Friederich “Fritz” Rosenbaum, a German-born Jew who established a successful career in San Francisco as a stained-glass merchant. In 1878, he and his wife Johanna purchased land from Charles and Caroline Krug, and constructed a “modern” Gothic-Victorian mansion on a knoll north of St. Helena. The area had become a celebrated escape when White Sulfur Springs was established in 1852 as the oldest warm-mineral water resort in Northern California. Well-to-do San Franciscans reached the town by taking a steamer across the Bay and then a four-mile train ride, which began stopping in St. Helena in 1868. By 1886, the population of St. Helena had swelled to 1,800 residents. (Today, it sits at about 5,500.)

In its original incarnation, the Rosenbaum’s wooden clapboard house was painted white, with a wrap-around porch and black-slate cupola, tipped with a weather vane. From day one, wine was part of the house’s identity. Fritz constructed a stone cellar so he could age rieslings and zinfandels, like those he made back in Germany. The wines that were stored on property gave birth to Johannaberg Cellars, which became one of the earliest bonded wineries in the Napa Valley.

The Rosenbaums had six children, two of whom, Fred Jr. and August, joined the budding family business. As Travel & Leisure chronicled in 2022, things quickly took a turn, with 23-year-old August dying suddenly under mysterious circumstances, and his mother, burdened with grief, passing three years later at age 48. August’s sister Bertha is said to have been stalked by a “Count Freyenstine,” who apparently attempted to murder her inside the house.

Over the years, several different owners occupied the house on the hill. There are rumors of it housing a speakeasy during Prohibition, of a doctor there doling out “medicines,” of it perhaps becoming a brothel. (In the late 1800s, the town of Napa developed a thriving red-light district that survived well into the next century.) The house fell into disrepair before being restored in the early 1960s, when the owners of St. Clement Winery purchased it. The Huneeus family bought the property in 2016 when they wanted to create a home for the wines of the Faust Estate vineyard.

The restoration project fell under the guidance of San Francisco architects Aidlin Darling Design, as well as the interiors vision of Maca Huneeus Design. It was clear from the beginning that the legend of Faust—and the journey from darkness to light that it chronicles—would inspire the look and architectural feel of the house. Says Maca Huneeus Design associate Ona LeSassier, who helped lead the project, “There was never any doubt that we would paint the house black. It just felt right.”

Before things got underway, LeSassier recalls exploring the house with Maca Huneeus. Crammed into the cellar walls, they discovered old laudanum and Prohibition-era bottles. “Definitely not wine bottles,” says LeSassier. In the main-floor office, there was a note on the wall: “Don’t worry, the ghost is friendly.”

When LeSassier and Huneeus climbed the pull-down ladder to the cramped cupola, they discovered a poem, scrawled on the side of the wall, signed by Mad Wolf Warrior. It read, in part: Great Light of Jesus Please Shine Down on the Ghosts And Spirits of Edward Bale And August RosenBaum and Johanna RosenBaum and Lead them All in peace.

When you’re curating a house named for the legend of Faust, perhaps this is all just fodder for inspiration. LeSassier and Huneeus decided the main floor would be painted in dark jewel tones, each room cultivating its own identity—the Study, the Library etc. “Faust is a house,” says LeSassier. “There’s no other way to interpret it.” The proudly different rooms would encourage guests to explore the property, each doorway revealing a new experience.

The house’s stairwell, wrapped in a two-tone, black-and-white mural, would symbolize the transition of ascent. On the second floor, architect David Darling raised the ceiling, opened up the cupola, and exposed the joists, creating a white-walled salon, awash in the bright Napa sunlight.

From darkness to light.

A house that is now, once again, a home.