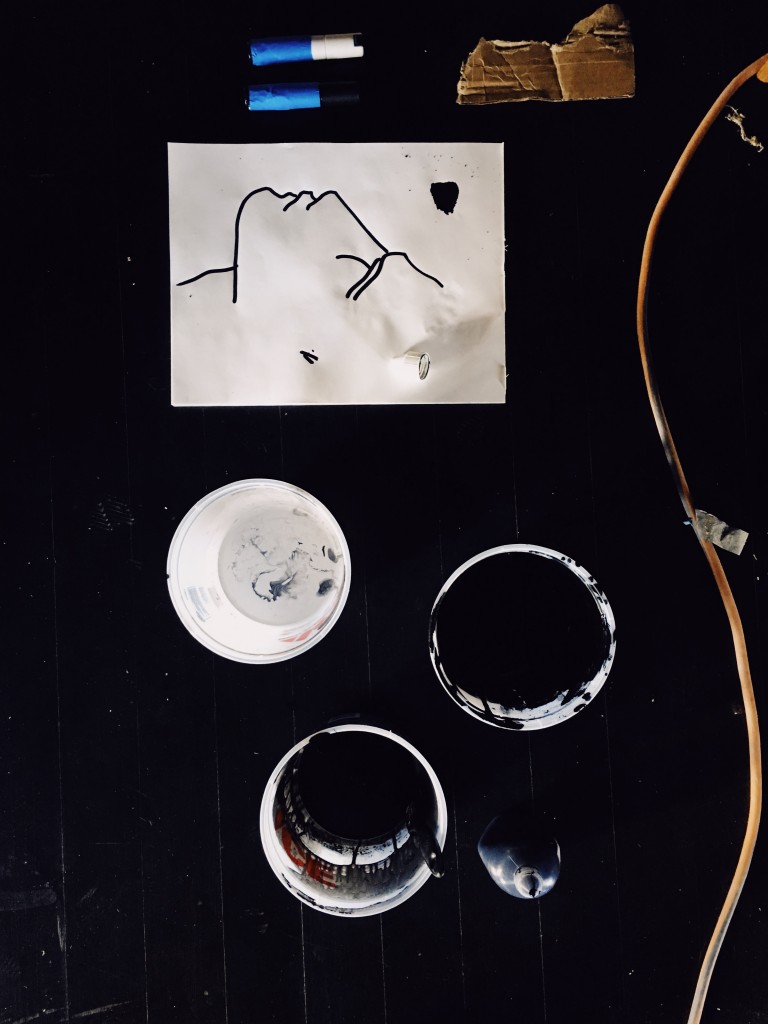

STEPPING INTO THE mind of Roberto Ruspoli is akin to entering a Grecian playland. It twists and turns and writhes like his brush strokes into places unknown to the conventional eye. It’s one full of whimsy and a studied levity but steeped in historical context, much like his airy Parisian studio in the city’s 14th arrondissement. In one corner, his endless charcoal studies of the human form are tacked and layered onto a sunlit wall, and in another, a selection of ceramic busts, in varied mediums, keep watch.

It’s clear that Ruspoli is influenced heavily by ancient Greek works, though he continually seeks a more modern interpretation of it. “It generates a form of harmony in me more than any other,” he says of the era. “It might be because I grew up surrounded by the classic world in Rome or that the classics were my main studies in school, but I feel it on an even deeper level.”

WHEN WATCHING RUSPOLI at work, his deep admiration and understanding of his subject is made even more apparent by the speed at which he produces a new piece. His brushstrokes are purposeful and don’t immediately point toward a completed work until it is, indeed, completed,and one finds that each wispy movement was done with particular intention. “It is almost a process of unveiling to me, a revealing of the shape I am feeling in that moment,” he says.

When it came to his work at the Faust Haus, Ruspoli opted to design an expansive charcoal mural that unfurls through the home’s entryway and up through its staircase. In it, one quickly notices several vignettes pulled from the legend of Faust, in which the story’s protagonist seeks unlimited knowledge and earthly delights, among them, of course, wine. “I look for the simplest symbols that are linked to the narrative to allow things to remain open and fresh,” Ruspoli says. “I wanted there to be a sense of movement and ascension.”

BUT FOR THIS revered artist, the difficulty is not in bringing life to a raw space, as was the case in the Faust Haus. Rather, it’s determining when a work is complete. “Understanding when to stop is the most delicate moment, and it’s not so evident,” he says. With this in mind, he has become a master in restraint, avoiding lines and shapes he deems unnecessary that could interfere with the purity of a viewer’s experience. “Usually, when you start to overthink, it means you should have stopped long before, so I tend to think closely about the design before I start and then just go with the flow when I start working,” he says of his freehand technique. “That’s the moment when you must fly.”