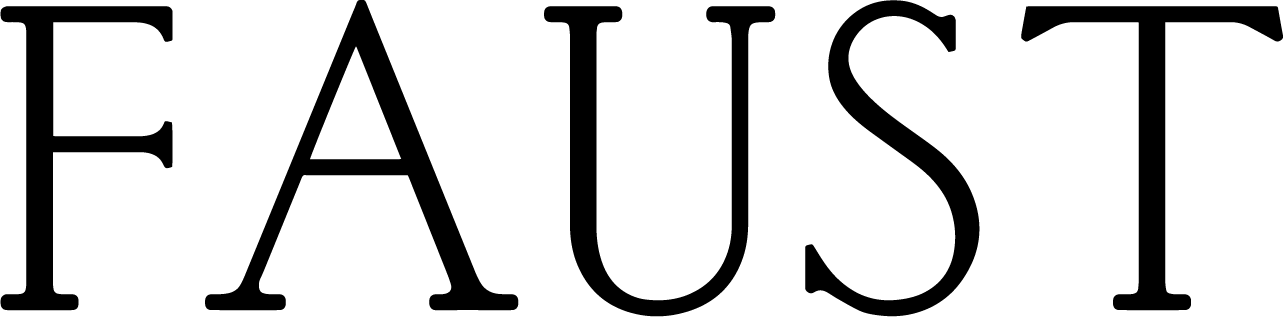

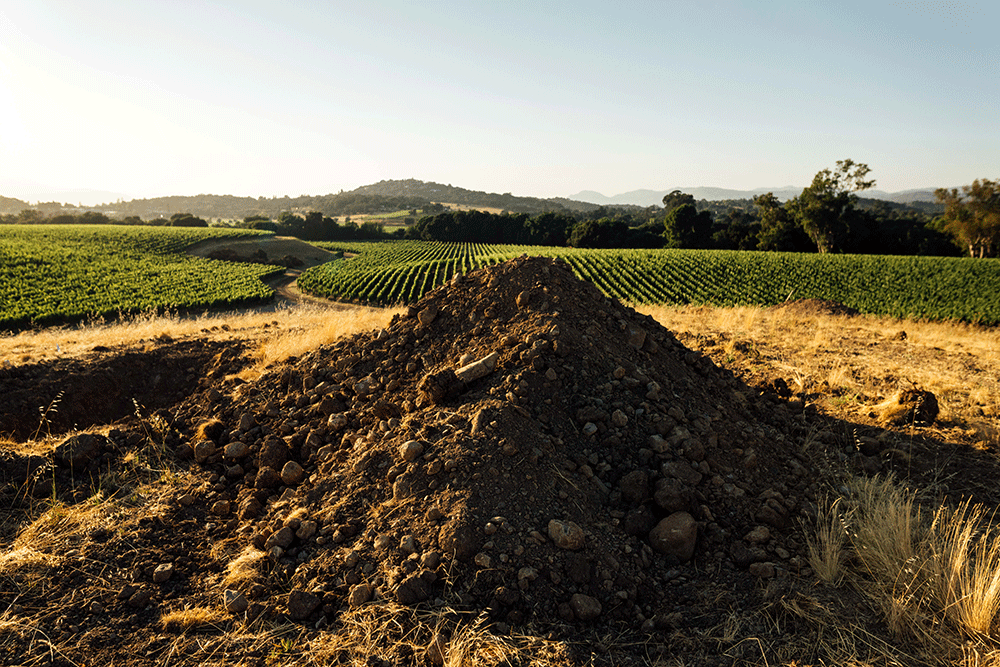

IT’S A BLUEBIRD SUMMER DAY in Coombsville, tempered by a gentle breeze, and a small part of the Faust vineyard is, quite literally, being turned upside down. Large piles of recently uprooted vines await removal. Scattered among the now-barren slopes are a series of deep pits dug with a backhoe, each one a little window into the geological strata beneath the rust-colored topsoil. Out of one of these pits climbs Faust estate director Jen Beloz, carrying a basketball-sized chunk of whitish rock in one hand, marveling at its lightness. It’s a piece of volcanic tuff, which is found in significant concentrations throughout this vineyard; it’s often interspersed with the large river stones and ilty loam deposits that characterize so much of Napa viticulture. till down in the pit, chipping away at the dusty white rock with is pocket knife, is Pedro Parra—a consultant of now-international renown whose stock in trade is digging trenches, mapping vineyards, and most important of all, drawing a through-line from soil to wine.

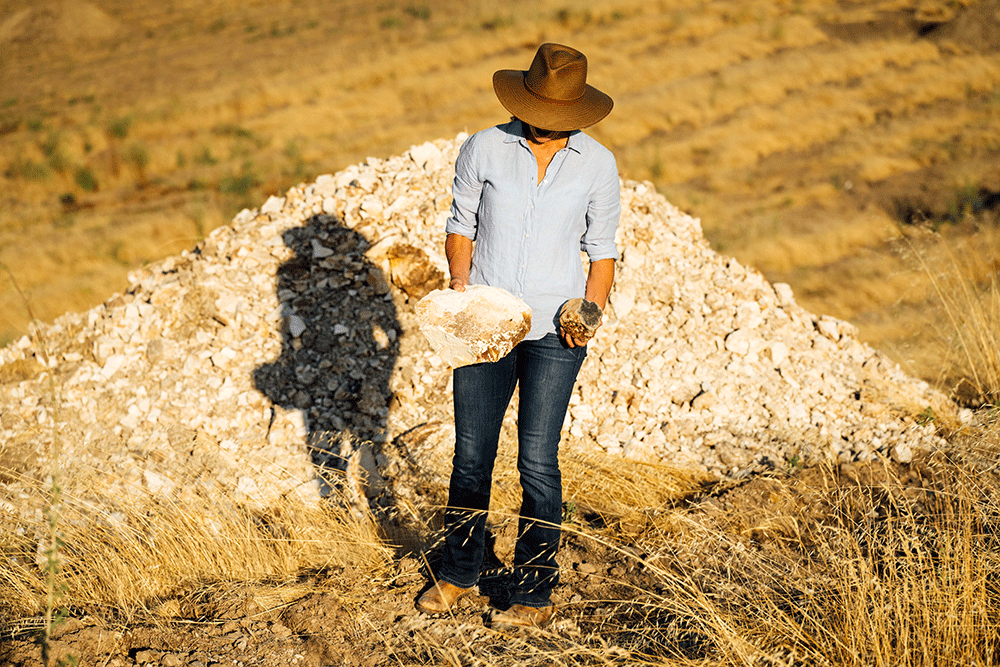

Ultimately, Parra will produce a series of soil maps for the Faust team, whose plan is to re-develop this section of the vineyard to support the evolution of The Pact. “We’ve been on a journey to really figure out the true potential of this vineyard,” Beloz explains. “And, as we replant, we want to be more precise about how to block it out.”

Enter the Chilean-born Parra, one of the more convivial, relatable scientists one is likely to meet. He has overseen the excavation of some 30 soil pits in a seven-acre area. Beloz and winemaker David Jelinek have been aiming to plant Cabernet Sauvignon in place of the Syrah and Petit Verdot that had previously occupied this section of the vineyard, as a means of augmenting both the quality and quantity of the Pact production in the future. Parra was brought in not only to help validate that decision, but to provide an actual map for the best way to go about it. But Parra’s not just a soil scientist, Beloz notes—his skill and accumulated experience as a winetaster are as valuable to her as the maps he was hired to draw.

“I’d describe him as a soil translator,” she says. “It’s the coolest thing to stand in a pit with him and look at the soil structure, then sit down and taste a wine from that site and listen to how he connects the dots. We’re sitting there with volcanic dust all over our hands, and we’re tasting wines from Coombsville that all share this kind of fine-grained, almost dusty tannic structure. It’s one thing to say it, and quite another to see it.”

Read up a little on Parra and you’ll hear similar refrains from some of the biggest names in wine, from Burgundy to Barolo to Napa and beyond. They invite Parra to come dig up their land, taste their wines, and offer opinions on what’s working and what’s not. They hire him to help them decide what kinds of wines they are going to make based on the conditions on the ground and, for all his self-effacing humor and unscientific language, they listen—even when he’s telling them something they might not want to hear.

Parra was born and raised in Concepcíon, in southern Chile, and while this coastal city is the gateway to the Bio Bío and Itata Valleys (two up-and-coming wine regions), his family was

not in the wine business, or even agriculture. His parents split up when he was very young, so most of his time growing up was spent with his mother, a noted law professor at the University of Concepcíon. His grandfather, Marcos, passed down a love of music and cinema so profound that Parra briefly considered trying to make a go of it as a musician. In his lively, occasionally digressive treatise/memoir, Terroir Footprints, Parra begins each chapter with a short discourse on an album or song (usually jazz) that he finds especially resonant. Music references factor prominently in any conversation with him, which is apt because, after seeing him in action, one is reminded of the enigmatic record producer Rick Rubin (minus the Santa Claus beard).

Rubin, who has worked in just about every musical genre and with a who’s who of artists, is neither a musician nor an especially skilled sound engineer. His “ear,” or sensibility, is what makes him a great producer. Likewise, there’s an element of “I know it when I see it” to Parra’s work, even though he has more technical fluency in his chosen field. He spent years studying agronomy in France, in both Montpellier and Paris, focusing on pédo-paysages (soil landscapes) and how to map them. His Masters is in “Geographic Information Systems” and his PhD thesis tackled the complex French concept of terroir, but his commentary when tasting is decidedly—and deliberately—unscientific.

The late Mark Tarlov, the film producer turned Oregon vintner, wrote a foreword for Terroir Footprints that cast Parra as a kind of guru, whose wisdom has included proclamations such as, “Look at where you are rather than where you wish you were.” John Hamel, a Sonoma vintner who has also worked with Parra, is similarly admiring. “Working with him really brought it all home for me,” Hamel says. “He’s able to identify and articulate the mpact of soil on wine in a way that is so unique. There’s really no one else who does what he does.”

At Faust, Parra participated in a comparative tasting of The Pact alongside wines from the estate’s closest neighbors in Coombsville. The goal was less about determining which wine was the “best” and more about drawing conclusions about the types of wines the Coombsville terroir is capable of producing. In Terroir Footprints and in person, Parra describes his wine-tasting methodology as “tasting by rocks,” meaning that he has become adept at identifying the type of soil a wine comes from based on the wine’s texture. On the many occasions he’s asked to participate in blind tastings, it’s the wine’s feel in the mouth—not its color, nor its aromatic profile—that produces the most correct guesses. First identify the place of origin, then the other identifying characteristics of the wine fall into place.

In the Faust estate vineyard, Parra’s pit-digging revealed two principal soil types: gravel with silt/clay/sand, and, often just a few yards away, the aforementioned white tuff. Clay soils, Parra says, typically produce “rounder” and juicier wines, whereas sandy/volcanic soils—which offer better drainage and thus force the roots deeper into the rock in search of water, produce “harder” wines. When asked whether he believes that the vines, which have circulatory systems, directly pull minerals from the earth and deposit those minerals in the juice of the grapes, he demurs. The scientist morphs into the philosopher. “I cannot prove it, but I can taste it,” he says. “The best machine to measure soil’s impact on wine is your mouth.”

Nevertheless, amid such aphorisms are some actionable nuggets for the Pact team, especially regarding “tannin management” of the Cabernet vines they intend to plant. Much as he appreciates the “tension” of the 2019 Pact, he remarks on the “dryness” of the tannins, and how a gentler maceration on skins during fermentation could help alleviate that. In a way, his tasting impressions are a kind of warning, to the effect of: If you want to plant Cabernet Sauvignon in that volcanic tuff, you need to beware of rough, dry tannins.

All of which is welcome news to Beloz, who isn’t at all fazed by Parra’s preference for one of the other reds in the comparative

tasting. “We definitely believe in this ground for Cabernet Sauvignon,” Beloz says. “But everything is up for discussion when we get Pedro’s map suggestions back. Everything is in play, from which varieties, rootstocks and clones we end up planting. And, who

knows, maybe it won’t all be Cabernet Sauvignon in the end.”

In recent years, Parra has added “winemaker” to his ever-growing list of titles, having established a wine estate in his native Itata

Valley. Very few, if any, wine consultants have such a diverse skill set, and to have him visit your estate and taste your wines is an

invaluable kind of peer review. As Beloz recalls, she and Jelinek went back and did the comparative tasting again after their first run-through with Parra. She remains fascinated, she says, by how Parra took a bunch of things she already knew—the presence of volcanic ash in the vineyard; the taut tannic structure of The Pact—and re-framed and re-presented the information in a way that was novel and, more importantly, useful.

“There weren’t any real surprises from his visit,” she says. “But we’re now equipped with a level of detail and understanding we didn’t have before. Between David and me, we have three science degrees, and still I feel like I’d like to go back to school and get a degree in soil science.”

Of course, for Beloz and Jelinek, we’re talking “wine years” here, which means it’ll be a long time before all this digging, studying, and tasting has any impact on the product in the bottle. The Cabernet Sauvignon they plant in this recently uprooted section of the vineyard may end up being the best Cabernet on the estate. But it may not all be Cabernet Sauvignon. There might be some Cabernet Franc, or Petit Verdot (or both). The answers are down there in those pits, amid the rocks and dust.