The Season Starts Underground

November-December

The first thing we do after harvest is nourish the roots of our vines. We irrigate the vineyard, flushing the roots to bring them nutrients harbored in the soil. We layer in more nutrients with compost. And we plant cover crops between rows—grasses and flowers that hold down weeds (no garden-sprayer Roundup for us). We deliberately plant cover crops that fix nitrogen in the soil to give the vines more power. Then we keep an eye on the winter rains— too little, and those cover crops steal the precious resource. While we like to let the likes of clover and legumes grow as long as possible between rows, in drought years we till them into the soil early to let as much water as possible filter down to the roots.

Time To Prune

January – February

Even before we know how much rain we’ll ultimately get, and how the season’s temperatures will play out, we make a pruning plan. In other words, we decide how tightly to cut back last season’s now bare, spindly shoots. We want to leave just the right number of buds, in the best position, to balance the grape crop we anticipate coming. It’s far from a vineyard-wide plan. The land is divided into “blocks” (from an aerial view, these look like so many rectangles and amoebas). Each might vary from another with distinctly different soils, aspects, elevations, and row orientations. As such, pruning ends up being a row-by-row, vine-by-vine decision.

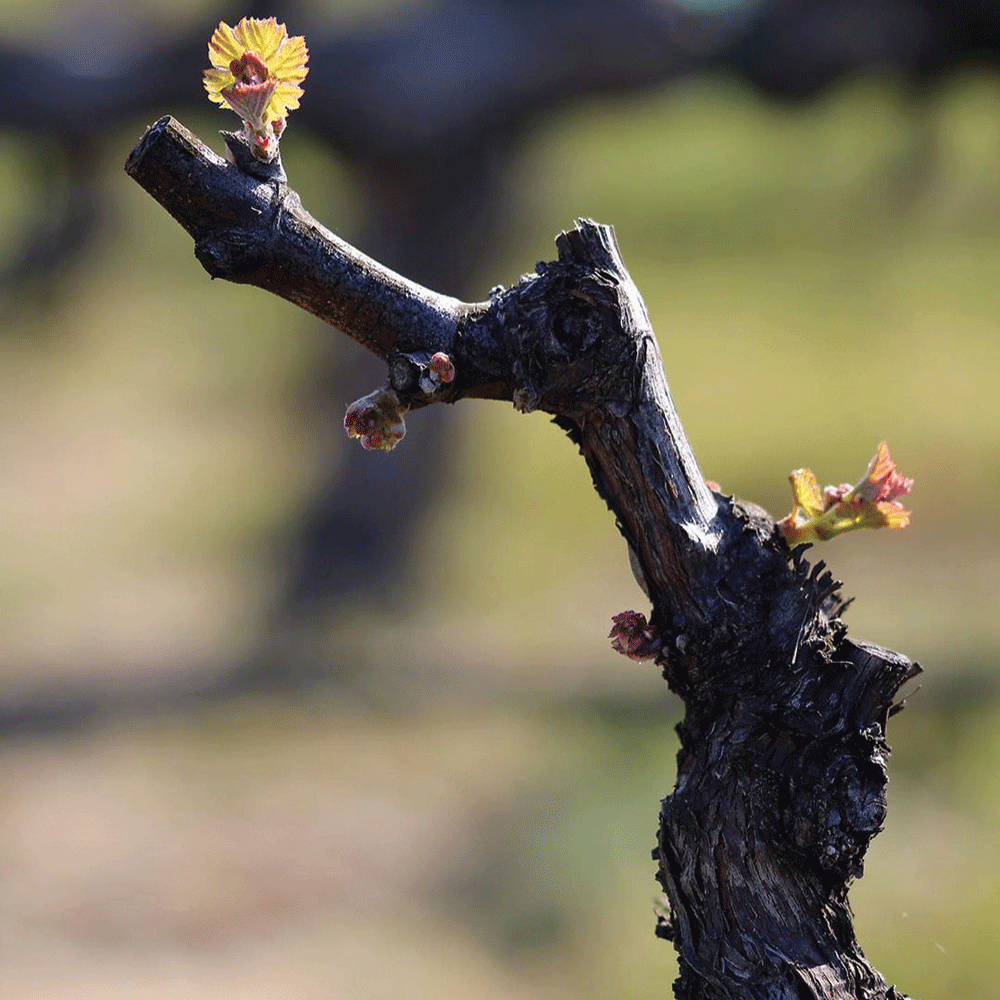

On Alert For Freezing Temperatures

March – early April

Come spring, we get to watch the vines come to life, as the first vibrant green growth appears on the bare shoots (“bud break,” in vineyard lingo). Our excitement is tempered by prayers we won’t get any late, deep frost that might prevent those buds from exploding into the shoots and clusters they are meant to be. If that happens, we hightail it into the vineyard and activate the overhead sprinklers that provide frost protection. They keep the temperature on the buds just above freezing even as ice forms around the water.

The Grand Period of Growth

Late April – May

As temperatures rise and vines spring into photosynthetic action, tiny blossoms appear. They in turn pollinate the shoots, and miniature clusters of tiny green berries follow, looking like so many Lilliputian Thompson seedless clusters on a dollhouse table. It’s time to take stock of the crop load, with an eye to the resources (moisture, canopy potential) each vine will have to draw on to ripen those clusters in perfect balance of sugar and acidity levels, phenolic maturity, and complex flavors. If the load already looks too large for the vine, our foreman Alberto Cuevas (pictured) and his colleagues remove weaker shoots, so healthier ones can fully develop—a process called “suckering.”

Managing Canopies

June

As canopies leaf out, nature’s plan is to protect the fruit from the summer sun. Our plan is to fine-tune that protection: open up the canopy to expose the fruit to some sunlight. Too little light gives aromas of bell pepper, too much sun intensity and overripe, pruney flavors dominate. Dappled sunlight nails that balance, so we pull individual leaves to achieve the effect. If we get it right, we get intense, pure, fresh flavors.